Responsible water management, throughout our built environment, is more important than ever. The planet is heating up, sea levels are rising, and flooding is increasing, while at the same time we must keep our cities and ourselves comparatively dry. Ironically, the natural environment may also offer a fantastic solution.

In this article, AKT II’s infrastructure director Dean Cadby explores the relatively recent concept of ‘sponge cities’ – and the approach’s apparent potential to soak up both water and developmental risk alike.

A tsunami of urban-development challenges looms, worldwide. The exact scenario varies with local geography, but the climate crisis and its constituent water-borne threats will certainly affect us all.

Flooding is getting worse. In the UK we’re experiencing more-frequent floods during winter (while summers are also getting dryer, with some Victorian-era reservoirs now drying up), while countries which historically have had very little water, such as in the Middle East, are now experiencing winter flooding also. London’s Thames barrier, which was delivered during the 1980s to protect the city from freak seasonal flooding, is today being activated twice as often.

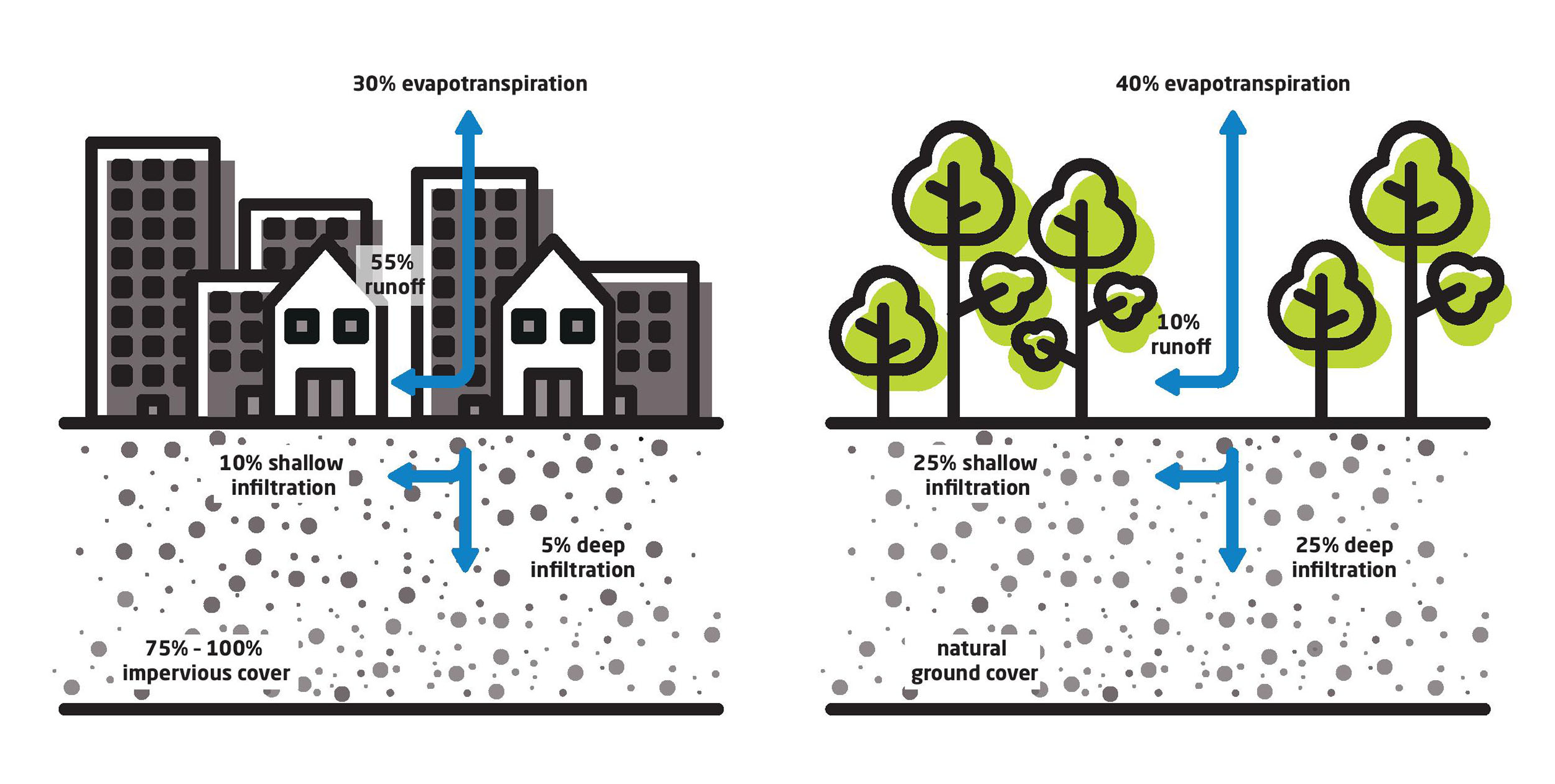

History has moreover taught urban designers to simply push water away from development as quickly as possible, and to then forget about it entirely. A traditional house features a sloped, tiled roof to move water efficiently into gutters, which flow into downpipes and then into sewers. Vast hardscaped developments have simply scaled this up. But the more we develop, the more we’re pushing water away from where it should be, and at some point the water is going to push back.

This traditional exiling of water from our urban development is a swelling problem. As our cities expand, we’re placing ever-compounding loads on drainage systems which eventually will no longer cope. Using the traditional ‘grey’ hardscape-heavy development of central London as an example, the rain has to go somewhere and so typically runs off into the Thames, which is now struggling for capacity. Higher water levels mean less available contingency for weather events before things start to overflow. And the weather is getting worse.

This unsustainable situation is further compounded with issues of contamination; in an overflow scenario the foul drainage often mixes with surface water, and will then contaminate rivers and harm ecology.

The key point here is water management, the embracing of which will bring great value to both development and future society.

It’s clear that we have to get all of this under control. Ideally, our built environment should mimic the natural one, which means soaking up the water – like a sponge – and getting this water into the ground locally i.e. where the rain falls, by infiltration into the soil. This is how the undeveloped landscape deals with water and it’s worked very well for a very long time.

Thankfully, we can look to several forward-thinking cities globally for inspiration. China has arguably led the way, with Wuhan being the original ‘sponge city’, where water is actively looked after and contributes to placemaking and amenity. These pilot areas are in fact designed to flood, i.e. are underwater during the winter and then function as dry landscape during the summer. The water, when present, is purified through natural and engineered means and thus supports many different community functions, including leisure and farming.

Back in the 2000s, AKT II designed one of the UK’s first 100% sustainable drainage (SuDS) schemes, for the Butterfield Innovation Centre in Luton, with Hopkins Architects. The project was praised for its pioneering relationship with water. An expanse of ‘blue infrastructure’ integrates around the business-park programme to attenuate and infiltrate any storm surges into underground aquifers, leaving zero discharge for local sewers. Workers gain a wellness and relaxation boost, while local wildlife flourishes.

Butterfield Innovation Centre.

Further great examples include BIG’s upcoming New York ‘Dryline’ – another linear park which this time wraps a rewilded, landscaped fringe around lower Manhattan, for flood defence. And in Malmö there are residential developments that feature ponded courtyards for rainwater storage and dissipation. Interestingly, and despite public apprehension around the idea of children growing up around ponds, we only need look to these Scandinavian communities to see that young people have been doing this for 100+ years and generally don’t (unintentionally) fall in.

In any location, there’s no point in taking landscape water from the mains when we can simply get it ‘free’ from the clouds and can then store it from the winter for use during future seasons. In addition to the obvious benefits of water management and flood control, these blue-infrastructure features promote biodiversity and human wellness, and when combined with greenery will capture atmospheric carbon too. On-site water collection and storage also creates opportunities for further design disciplines, and for example can be used to supply building services, and even for thermal storage. The benefits of blue design are widespread, and really are profound.

In many cities there is furthermore a great, as yet untapped opportunity to improve the public appreciation and receptivity for such water-integrative provision. Flooding becomes a good thing once we’ve designed our built environment not to fear water, but to welcome it.

So, at AKT II, our go-to strategy on any project for a long time has been to look for ways to retain and incorporate water throughout the design. We’re excited to see this thinking increasingly reflected in competition briefings, which no doubt will be bolstered by the pandemic’s highlighting of the importance of wellness where we live. Through many relevant projects, we’ve developed a blue-infrastructure ‘kit of parts’ that allows cross-discipline teams to efficiently implement blue design throughout any new or redevelopment scheme.

Maggie's Yorkshire has been fully integrated into the landscaping.

We must make friends with water. We can’t turn back the clock on climate change, but we can encourage our industry to take advantage of the unprecedented opportunity that these extreme circumstances have precipitated.

In the UK, the government has already allocated a site for a second Thames barrier, with an anticipation that the first one may not be enough to hold back greater flooding of the future. We must step up, and must take responsibility for this very same water throughout all of our urban designs.

We are facing an imperative to transform our built world with a new model of infrastructure: one which at the same time offers the potential for fantastic environmental, economic and social longevity.

All of these insights and ideas are already being explored by AKT II Infrastructure, as part of developing creative to crack even the most complex sites.

To learn more about the value that AKT II Infrastructures brings to projects the world over, get in touch to see how we can help.

AKT II Infrastructure Engineering The JJ Mack

The JJ Mack The Farmiloe.

The Farmiloe. 2–4 Whitworth

2–4 Whitworth White City

White City  NXQ

NXQ TTP

TTP One

One The Stephen A. Schwarzman

The Stephen A. Schwarzman