The new residential redevelopment Regent’s Crescent sits at the northern culmination of Regent Street and Portland Place, and gives identity to London’s West End. Embodying many years of history and intrigue, it’s exemplary as one of our most satisfying projects to date. Maria Camporro, our lead on the project, here details the story behind the restoration and reconstruction of the Grade I-listed façade; exploring the bones of the structure, and the ingenious solutions that have made it all happen.

Part of why this project is so special is because we’re making history – by rebuilding a Grade-I listed façade. A combination of wartime damage and poor restorations has presented us with an opportunity to reconstruct the iconic, John Nash-designed Park Crescent. Through sophisticated diagnostics and engineering technology, this unique masterpiece of Georgian design is being restored and transformed into a postcard civic architecture for the 21st century.

The existing crescent was designed in the early 1800s and completed in 1820. The architect’s vision was to create a link between Regent’s Park and the (smaller) London of that time, and while this crescent is one of 66 throughout the city, it’s special because it’s the imagination of the same architect as Buckingham palace.

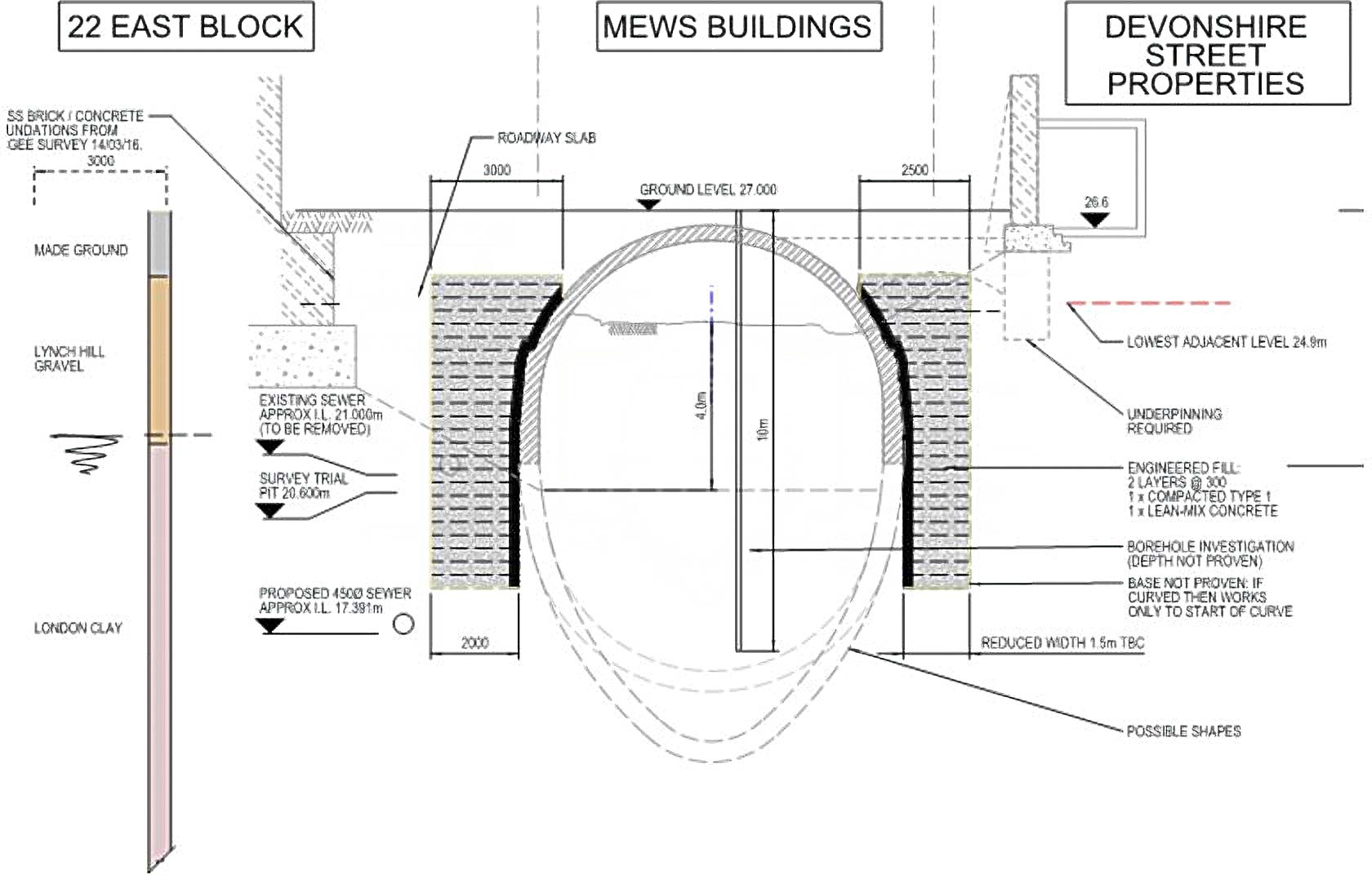

The site notably contains a subterranean icehouse, built by Samuel Dash circa 1780 and later acquired by the ice merchant William Leftwich in the early 1800s. During London’s Victorian era, this brick-lined vessel stored ice shipped from Norway for the city’s aristocracy, but it was then covered at some point in the original crescent’s construction, and subsequently forgotten for over 150 years.

In 1947, following the Second World War and despite the severe bombing damages to Park Crescent, it was decided to retain the crescent at all costs. The stucco façade – partially destroyed by the bombs – was to be reconstructed in its original detail, in an attempt to preserve the classic style of Nash’s original architecture.

During this 1960s reconstruction work, the icehouse was uncovered but then rapidly filled with rubble – disappearing again.

Four principal challenges were faced by our engineers, in the structural design of the new Regent’s Crescent.

The most significant challenge was the façade reconstruction, where our team was tasked with achieving historical accuracy while also meeting modern performance requirements. Working closely with the architect PDP, alongside English Heritage, Westminster City Council, and conservation specialist Donald Insall Associates, we collectively decided to attempt the first-ever Grade I-listed façade re-build, under the leadership of client CIT.

Maintaining the 120-metre-long brick structure was an unprecedented feat in London, and not least because the original construction contained no movement joints, whereas modern design guidance would limit any such section to around one-fifth of this length.

In order to confront the challenge of replicating the iconic heritage façade, the design team had to undertake extensive research and analysis. Through measures including the specification of ‘good old’ lime mortar, in conjunction with laboratory testing during the brickwork installation, both of the above objectives have been achieved: a modern solution, and incorporating a centuries-old construction technique that only now is better understood.

During the designed life of a typical building, the key causes of façade movement include moisture expansion as well as thermal expansion and contraction. With this in mind, we sourced bricks that were already old enough to have achieved 50% of their total expected moisture growth, and we also carefully controlled the bricks’ temperature during bricklaying to help mitigate the effects of seasonal change.

At the design stage, these innovations reduced the façade’s global movement, but the building’s predicted expansion and contraction were still greater than ideal. As a further solution, low-friction membranes were introduced at the façade’s base to reduce the differential movement between the bottom and top. Potential cracks at points of high stress were also minimised by the introduction of modern, steel-tensile reinforcement within the horizontal joints.

To meet modern performance criteria, thermal insulation must also be integrated within the design. To achieve this, we separated the heritage façade from the building’s frame, which means that, while the façade’s brickwork is self-supporting over five storeys, it retains cavity-wall characteristics for lateral movement and restraint. Bespoke brick-ties accommodate the expected movement while restraining the heritage façade against the steel inner leaf.

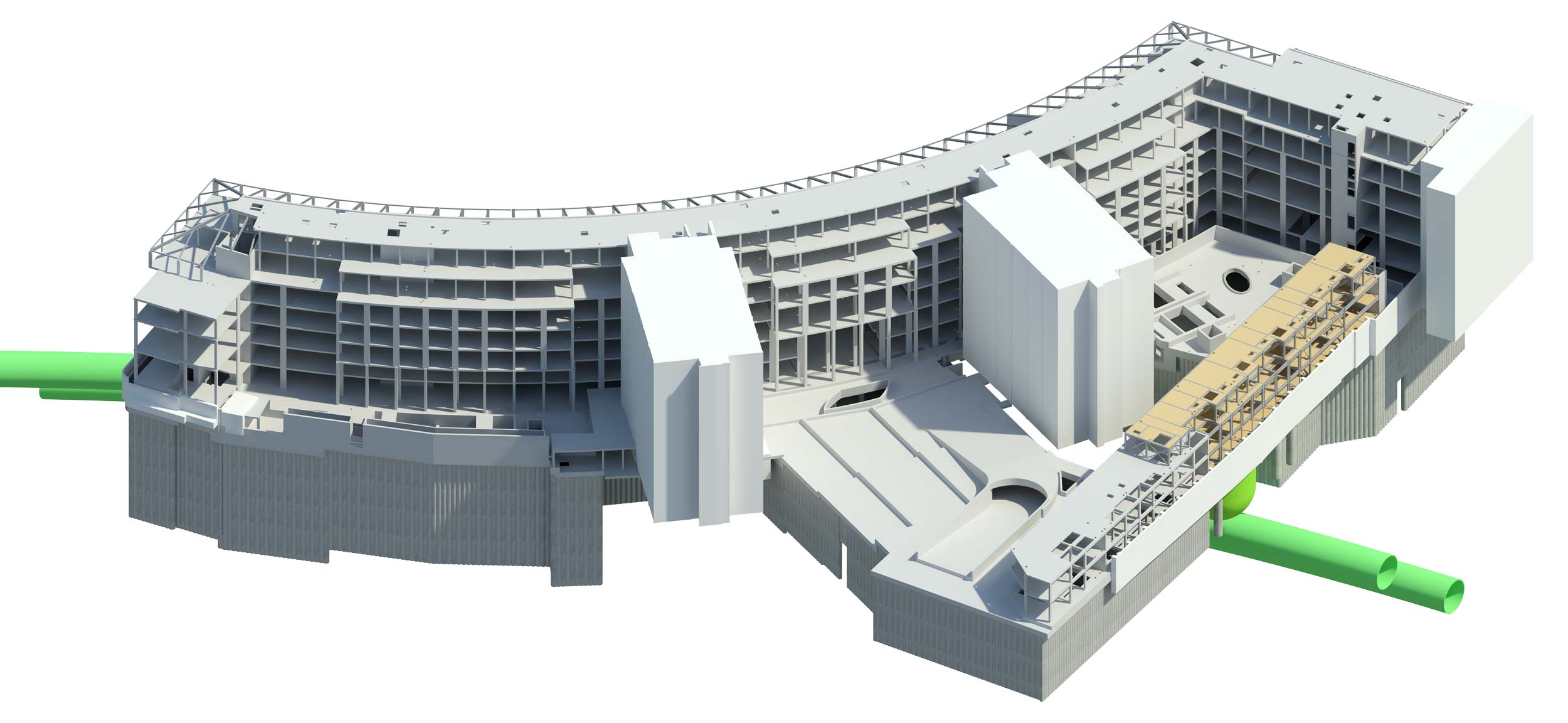

The building’s primary structural system offered the second challenge. The design must be flexible for the high-end residential market – which relies on high ceilings and outstanding amenity spaces – while also integrating with the complex site conditions.

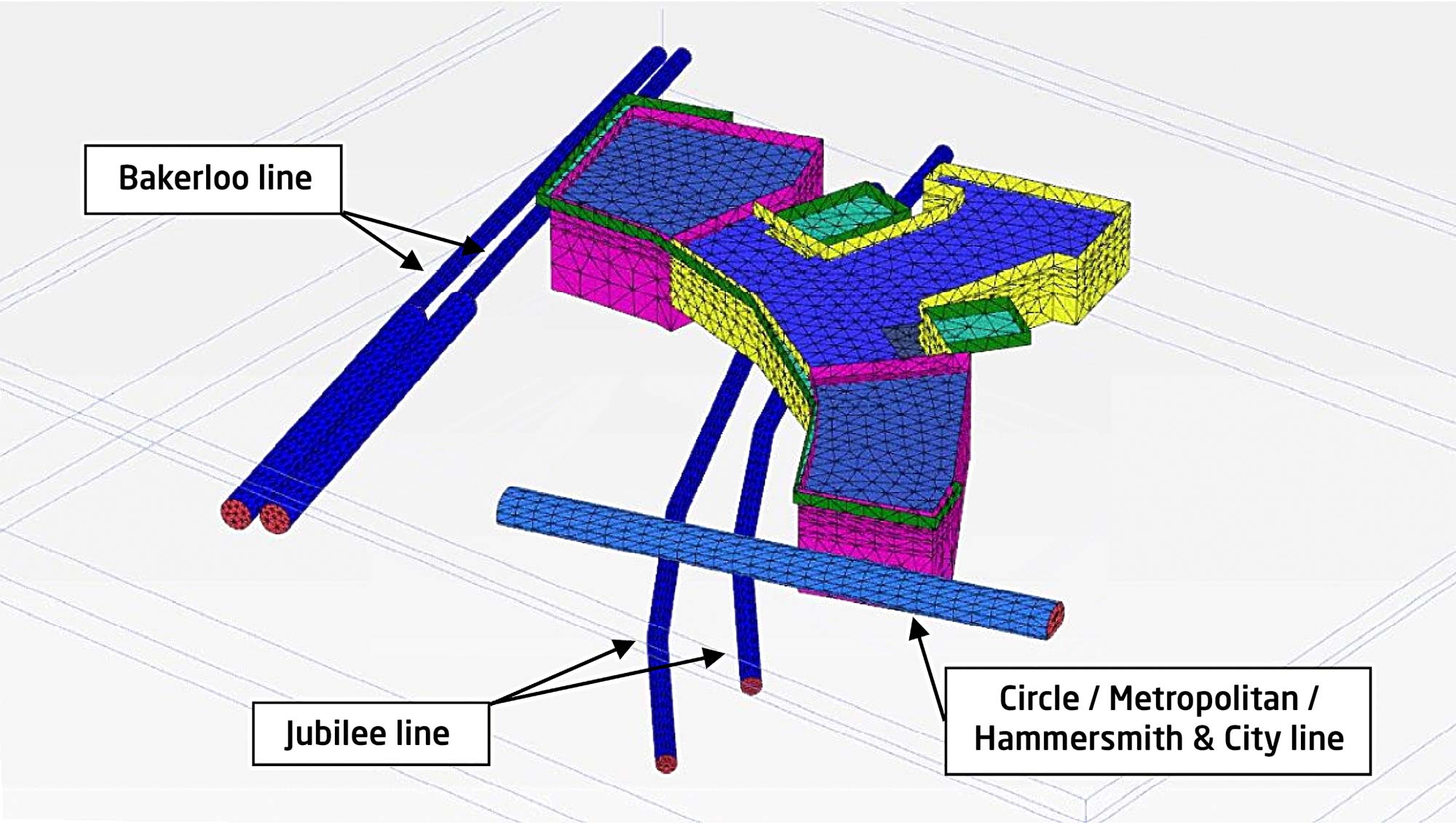

Not one, but three underground lines travel close to the Regent’s Crescent development: the Bakerloo to the west, the Metropolitan to the north, and the Jubilee passing directly beneath the site. To isolate the building from this ground-borne vibration, a system of acoustic bearings is installed between the basement and the residential storeys above.

Challenge three was the requirement to design and deliver a deep basement. While the development lies above the Jubilee Line tunnels, there are two existing residential blocks located in the middle of the construction site. These 1960s-built, eight-storey buildings have been occupied throughout construction, with the works incorporating temporary access for residents.

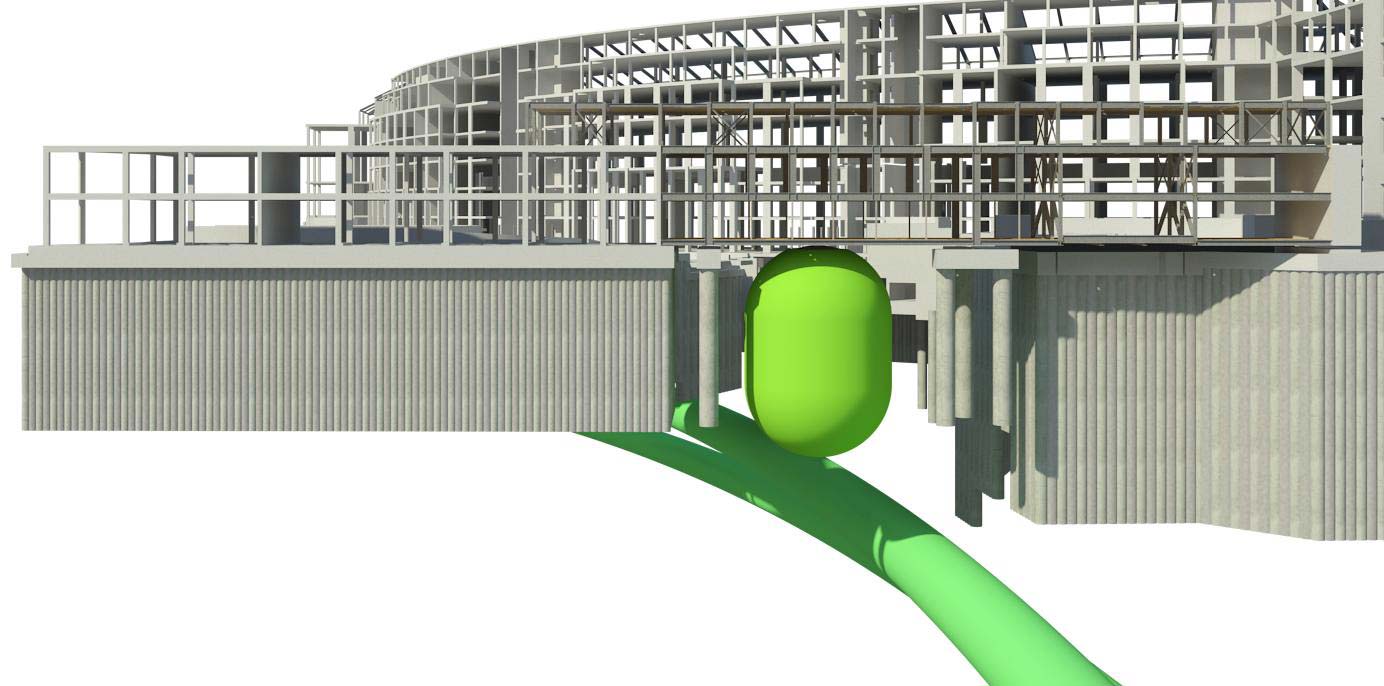

Challenge four is perhaps the most technically challenging of all, and arises from the team’s ambition to recover the historic icehouse structure. This involved removing the rubble from inside while preserving the structure’s integrity, and while also constructing the large new development directly above. The development’s planning approval also stipulated, within its conditions, that the egg-shaped icehouse must be made newly accessible.

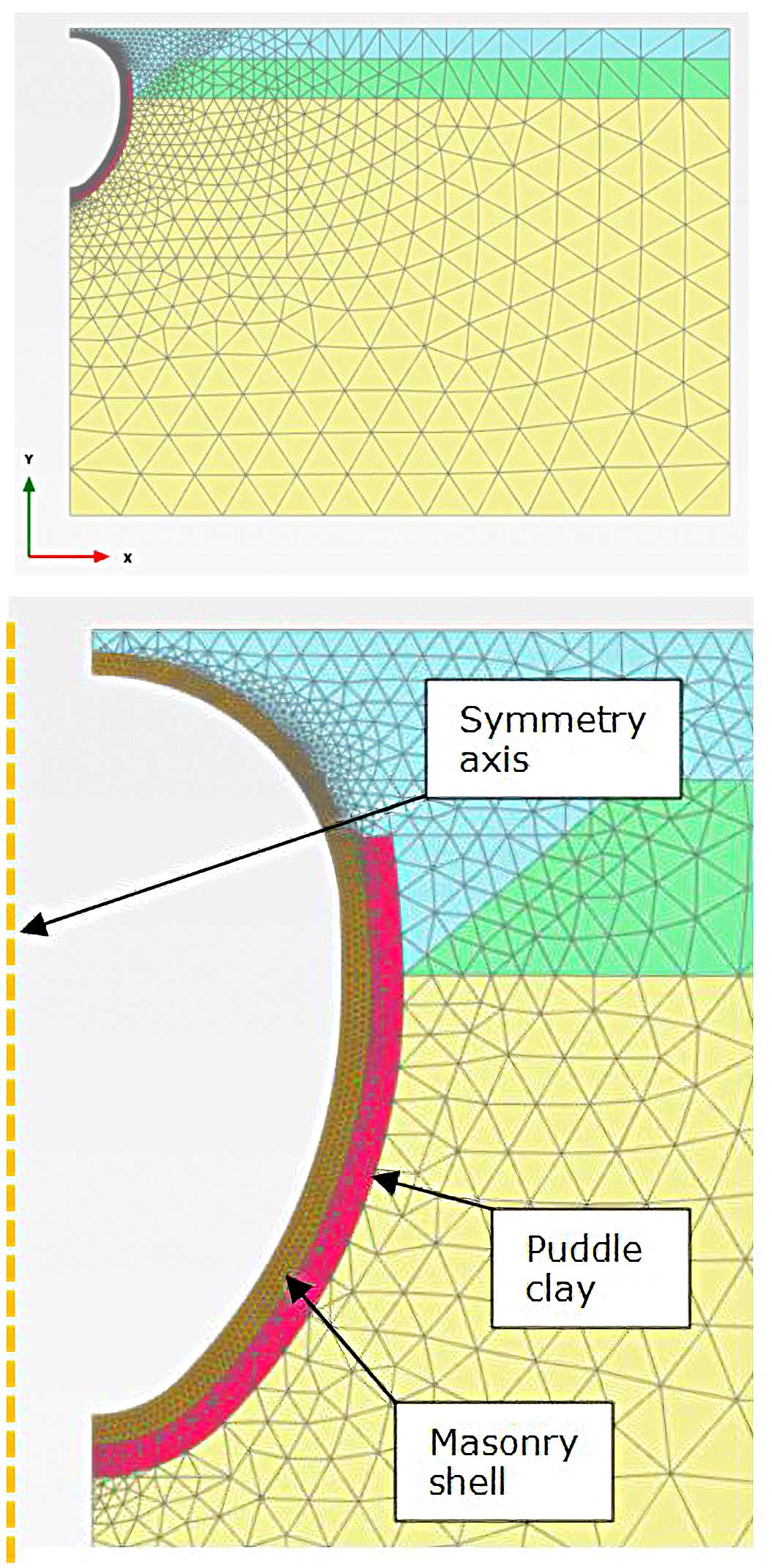

Any damage to this scheduled ancient monument would be a criminal offence, and so the team had to undertake careful structural and geotechnical analysis to devise the best preservation solution. We carried out a time-history analysis to evaluate the stresses upon the icehouse at different points in its history, ranging from the 1960s above-ground construction works to the present-day removal of debris.

Building over and around the icehouse was difficult. Any new structure must bridge over an exclusion zone that’s stipulated by Historic England, while any introduction of new load into the surrounding soil is a further risk, which must also be minimised.

Our solution applies full-storey-height trusses in both elevations, each spanning 17 metres to bridge over the buried asset, in conjunction with a lightweight structure throughout the building above. Within the residential levels, cross-laminated timber (CLT) floors reduce the overall structural weight by 65% compared with traditional concrete fabric; further minimising any risk of damage to the icehouse below.

Post-assessment, and with Historic England’s approval of our design, we were able to begin working on the critical stage of removing the debris that had until then filled the icehouse structure. Given the age of this designated ancient monument, there was a concern for the bricks’ quality and integrity, but during the debris removal the brickwork was found to be in excellent condition.

During this process, a German helmet from WWI was found inside. This helmet’s picture was later used by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) to commemorate the 2018 Remembrance Day – marking the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War.

Through clever engineering, the reconstructed façade of Regent’s Crescent delivers luxurious residences inside and out, while preserving the new development’s aesthetic alignment with the rich history of London.

Client: Regent’s Crescent Property Holding (Lease B) Limited

Architect: PDP

Conservation specialist: Donald Insall Associates

Engineer: AKT II

Development manager: CIT