‘Ipsa scientia potestas est’ – knowledge itself is power. We can observe this easily when we look at the role of the library throughout history. In this article design director Valentina Galmozzi and senior engineer Danae Polyviou detail how libraries have evolved and adapted through the centuries, from the ancient world to our modern era.

In the ancient world, libraries were usually linked to sacred temples or powerful rulers. The library didn’t just store manuscripts and books. It hosted lectures, where public speakers were invited to impress. Intellectuals gathered to discuss matters with visitors in the calmness of the library’s open halls and gardens.

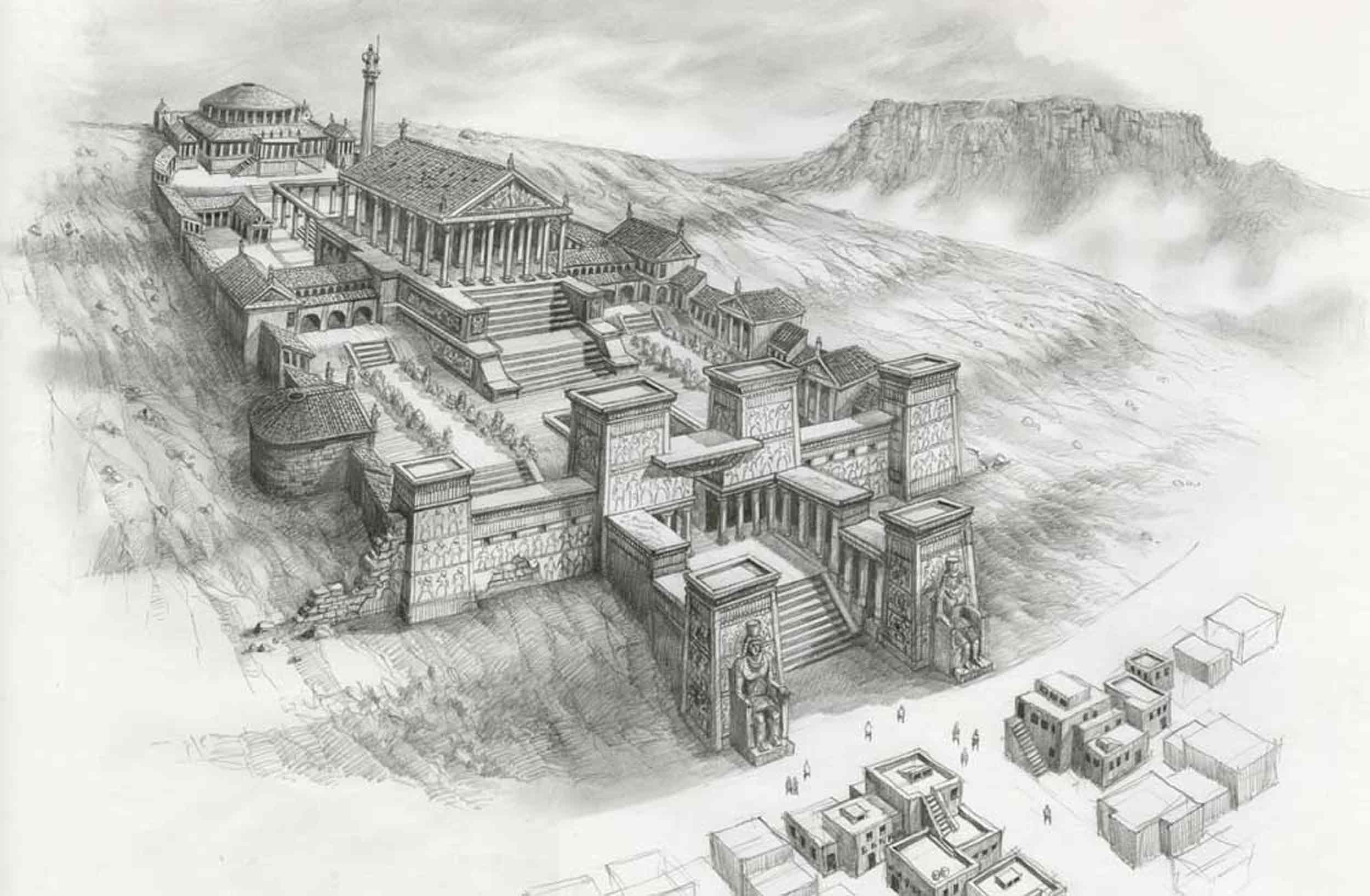

The earliest recorded library is that of Aristotle, which later became the Great Library of Alexandria. It contained the ancient era’s greatest collection of manuscripts, and more than half a million papyrus rolls. Alexandria was considered the knowledge and learning capital of the ancient world, in part due to the Great Library’s presence. The institution attracted some of the era’s foremost intellectuals and thinkers.

Historic sketch of the Great Library of Alexandria

Libraries enhanced a city’s prestige, and provided practical assistance in matters of ruling and governing the kingdom. Eventually, and for these reasons, every major Hellenistic urban centre developed its own royal library. Moving further north, the Roman emperor Pollio materialised what Julius Caesar had sought for a long time: a public library to increase the prestige of Rome, and which could rival the Great Library of Alexandria.

During the following centuries, the private book collections of wealthy and influential rulers began to flourish. Most of these collections would form the basis for a public library at a later date. New cultural factors, including the growth of commerce, the new learning of the Renaissance, the invention by Johannes Gutenberg of a printing press using movable type, and the substantial expansion of lay literacy, together widened the circle of book collectors to include wealthy merchants – quite a contrast with the funding cuts to public buildings in our present day.

The positive effect to the locales of these buildings is clear, even in modern society. A library’s presence can widely uplift the local urban fabric and community value – an effect that we’ve witnessed first-hand with the Peckham Library. Completed in 1999, and designed by the late Will Alsop, this unique and striking building brought inspiration and prestige to its local south-London community. Amidst a deprived inner-city enclave with myriad social problems, a new library might hardly seem a priority, yet Alsop’s dynamic building put Peckham back on the map. It became a gathering place, where people from differing socio-economic classes sit together, side by side.

The RIBA Stilring Prize-winning Peckham Library designed by Will Alsop.

In its first year, Peckham Library welcomed half a million people through its doors, and later received the prestigious RIBA Stirling Prize. Its inverted L-shape quickly became a local landmark. The distinctive building signified a wind of change, and changed our perception of what a library ought to be. The main reading room is suspended 12 metres above the ground, cantilevering from the concrete frame through long-span trusses, to provide readers with views over London. Concurrently, the public space created below the soffit serves as a new pedestrian hub.

Pods inside Peckham Library

Suspended pods within Peckham Library

Many people perceive libraries as quiets buildings that house books. Such a typology could perhaps be considered redundant in the post-pandemic epoch, as we move rapidly into the digital arena. But this conclusion can be very quickly renounced. Our experience shows that, when well designed, the library’s role is not lapsing but expanding. Reimagined through the lenses of its multiple offerings, the library is a space where the spatial, technological, intellectual, cultural and social can integrate, and where these design qualities can inform one another.

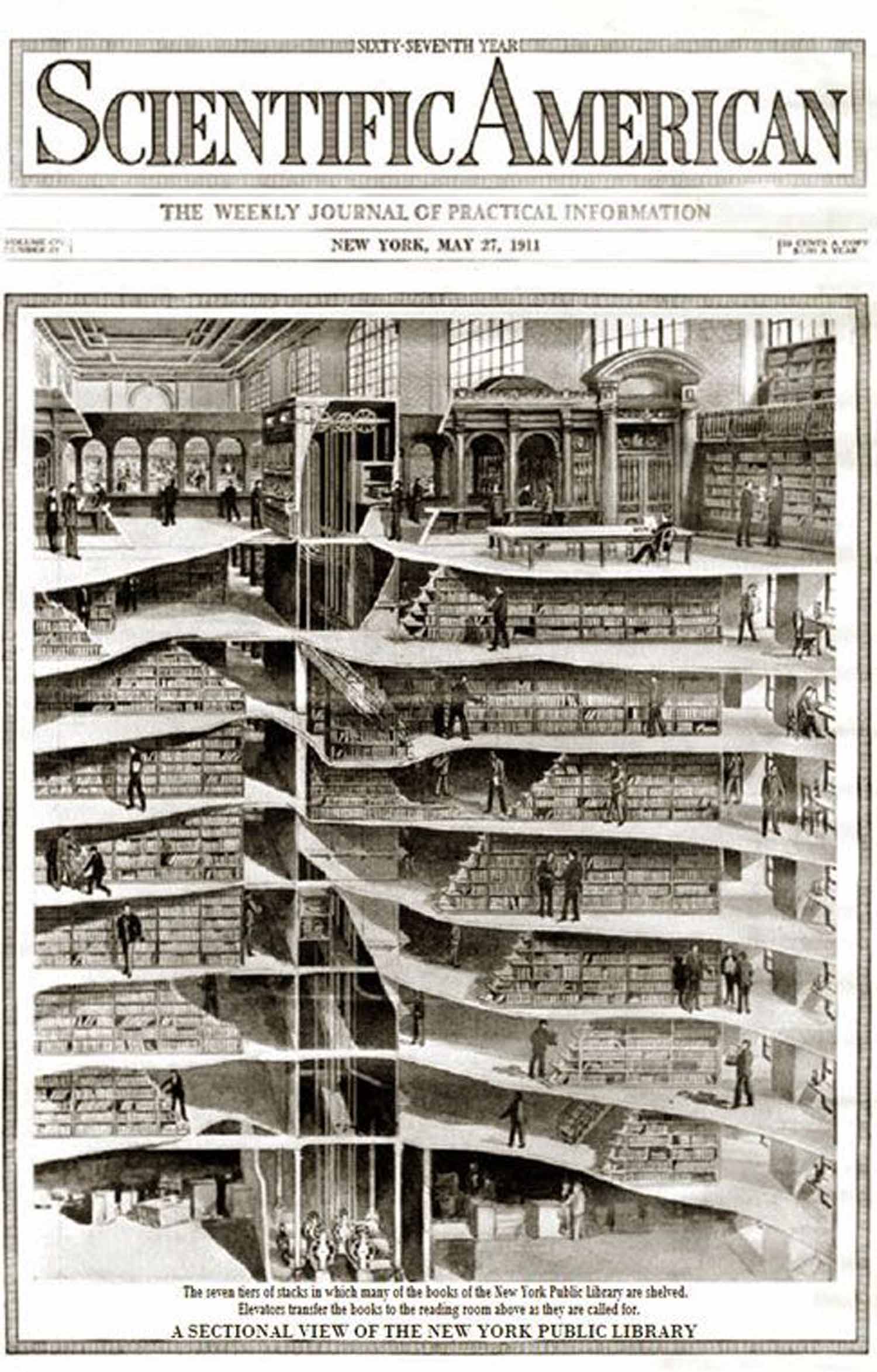

The cover of Scientific America circa 1911 depicting stacks at the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, New York Public Library.

The LSE Library (the London School of Economics and Political Science) is a designated United Nations depository library and the national social-sciences library of the United Kingdom. Over four million books are safeguarded within this facility. Originally constructed in 1914, the building was converted to a library in 1973, before being wholly redeveloped by Foster + Partners in 2001: a new central atrium, topped with a half-dome skylight, introduces daylight deep into the interior. The collections are reorganised by national or international importance, while an exhibition space within the library showcases these unique collections in a year-round programme, freely accessible to the public.

In 2004, the Seattle Central Library – a striking new building by OMA – redefined a library’s role within our modern world. The project is seen not just as a space for accommodating manuscripts, but as an institution where old and new media are blended together, offering a 360-degree experience for visitors. In the architect’s words: “It is the curatorship of their content that will make the library vital”.

Internal view of the Seattle Public Library.

In east London, the inverted-pyramid form of the Canada Water Library has perched on the edge of Surrey Quay Docks since 2011. The building embodies the first phase of a visionary quest to create a new town centre for the city. The design meets the demands of a challenging brief, with inclusivity for all users – adults, children and young people – through carefully crafted spaces. Rather than diminishing the ground-level public space, the building expands the experience of the people who use it.

It would be somewhat belittling to propose that a library’s services can be sourced online. Our experience shows these buildings to be fundamentally experiential and social. Far from being limited by the combination of facilities offered, the library offers immense design possibility.

In our current, ‘smart’ technological era, our libraries are far from obsolete. Technology can enhance the design of library spaces, not just architecturally, but contextually to reflect the quality of the local community.

Whether micro or mobile, national or local, or operated by robots or AI: today’s libraries are just a step in our design journey toward the icons of tomorrow’s architectural world.